Day 2, Tuesday 22 August: The salt of the earth

Dr Clare Sansom, Department of Biological Sciences, Birkbeck College, London, UK

What links the history of crystallography, Gandhi, the Indian chemical industry and the Guinness Book of Records? Unless you keep an exceptionally strict diet, you have probably eaten some today. It is common salt, which most people will remember from high school by its chemical name: sodium chloride. This humble compound was the subject of the fascinating session that kicked off the IUCr Congress parallel programme. This programme has been designed to highlight aspects of crystallography and structural science that don’t fit into the rigid structure of plenaries, keynotes and micro-symposia that comprise the main event. ‘The salt of the earth’ fitted that bill extremely well.

What links the history of crystallography, Gandhi, the Indian chemical industry and the Guinness Book of Records? Unless you keep an exceptionally strict diet, you have probably eaten some today. It is common salt, which most people will remember from high school by its chemical name: sodium chloride. This humble compound was the subject of the fascinating session that kicked off the IUCr Congress parallel programme. This programme has been designed to highlight aspects of crystallography and structural science that don’t fit into the rigid structure of plenaries, keynotes and micro-symposia that comprise the main event. ‘The salt of the earth’ fitted that bill extremely well.

Common salt was chosen as a session topic to celebrate, of all things, a world record: the largest model crystal structure ever built. Robert Krickl, a freelance science communicator from Vienna, Austria, spent a year of his life building a 3’ x 3’ x 3’ model of a salt crystal, with its constituent sodium and chloride ions represented by red and white balls. One third of this structure will be sitting in the HICC foyer throughout the meeting. Krickl gave the first talk, and he began by explaining the inspiration behind his model. He moved into science communication following a PhD in crystallography communication and had made something of a name for himself with travelling exhibitions by the International Year of Crystallography (IYCr) in 2014. Asked then to ‘do something about it’ he was single-handedly responsible for Austria’s second place in the table of countries’ involvement in IYCr, touring the country with an exhibition and giving presentations at 182 schools. His plan to build the largest-ever model crystal structure was announced at the very end of the IYCr closing ceremony.

Common salt was chosen as a session topic to celebrate, of all things, a world record: the largest model crystal structure ever built. Robert Krickl, a freelance science communicator from Vienna, Austria, spent a year of his life building a 3’ x 3’ x 3’ model of a salt crystal, with its constituent sodium and chloride ions represented by red and white balls. One third of this structure will be sitting in the HICC foyer throughout the meeting. Krickl gave the first talk, and he began by explaining the inspiration behind his model. He moved into science communication following a PhD in crystallography communication and had made something of a name for himself with travelling exhibitions by the International Year of Crystallography (IYCr) in 2014. Asked then to ‘do something about it’ he was single-handedly responsible for Austria’s second place in the table of countries’ involvement in IYCr, touring the country with an exhibition and giving presentations at 182 schools. His plan to build the largest-ever model crystal structure was announced at the very end of the IYCr closing ceremony.

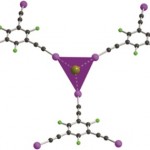

The choice of sodium chloride was an obvious one for Krickl; his model was built in 2015, exactly 100 years after the father-and-son team of W.H. and W.L Bragg were awarded the Nobel Prize for determining the crystal structure of this compound. A century later Krickl set about the task of acquiring the 38880 coloured balls and over 10km of sticks that he needed. The final model has repaid all his hard work, intellectually if not yet financially. If you look into it from different angles you will see an astonishing range of beautiful, symmetrical patterns. It can be disassembled so small parts can be displayed in museums or taken into schools. And the 25th IUCr congress in 2020 will be held in Prague, only about 300km from Vienna. Krickl might take his complete structure there; or, perhaps, he could challenge delegates to build a more complex model there.

Each of the four talks that followed explored a different aspect of salt: in the history of India and of crystallography, in contemporary science and in industry. Dinkar Joshi, an expert on the life of Mahatma Gandhi, described the history of salt taxes in India under the British Empire as a background to Gandhi’s famous ‘salt march’ of 1930. At the time, Indian salt was taxed to encourage Indians to buy imported salt that had been brought in as ballast for ships. Gandhi had written to the Viceroy with 11 demands, one of which concerned the salt tax; when he received no reply, he chose the salt issue for his ‘satyagraha’ (civil resistance) because of its importance to all Indians. Twenty-eight marchers, ranging in age from Gandhi himself at 61 to his teenage grandson, marched for 24 days to gather salt illegally at the coastal village of Dandi in Gujarat; the rest is history.

Mike Glazer from the University of Oxford, UK, vice-president of the IUCr explained the role that sodium chloride had played in the Braggs’ discoveries. It was not the first compound to produce a diffraction pattern (of sorts) in a beam of X-rays; that honour had gone to copper sulphate, a few years earlier. It was, however, the first to produce a diffraction pattern that was good enough for a correct structure to be determined. Interestingly, potassium chloride (KCl), which has the same structure, produced a different type of diffraction pattern because potassium and chloride ions have the same number of electrons and were therefore ‘seen’ as equivalent by the X-rays. The Braggs’ structure showed sodium chloride to be a ‘pure’ ionic compound, less than 20 years after the discovery of the electron. This was much to the chagrin of some chemists who had expected to see ‘molecules’ in the structure: but the rest, again, is history.

The final two talks brought the subject up to date. First, Artem Oganov, a solid state chemist with positions in both New York and Moscow, explained some of the properties that common salt’s ‘3D chessboard’ type cubic structure give to the many other compounds that share it. He took examples from centuries of solid state chemistry, taking the story right up to the present day and his own work. Among the structures he mentioned was a novel form of boron named gamma boron, in which small and large clusters of atoms replace the sodium and chloride ions on a cubic lattice; this is one of the hardest substances known. And finally, Amitava Das, director of an Indian government lab in Bhavnagar, described the vitally important role that common salt plays in the Indian chemical industry and thus in the country’s economy.